Fritillaria is a striking and diverse genus of spring-flowering bulbs, celebrated for their elegant, nodding, bell-shaped blooms and, in some species, their remarkable checkered patterns. The most famous, Fritillaria meleagris—often called the snake’s head fritillary—features petals in shades of deep purple, pink, or white, each adorned with a unique chessboard pattern. But the genus is far more varied than many realize. Other notable varieties include Fritillaria imperialis, or crown imperial, with its tall stalks and dramatic whorls of orange or yellow flowers topped by a tuft of leaves, and Fritillaria persica, which produces spires of dusky purple, almost black, bell-shaped blooms. There’s also the petite Fritillaria michailovskyi, with its maroon and yellow-tipped flowers, and the rare Fritillaria camschatcensis, known as the chocolate lily for its deep brown blossoms.

Fritillaria thrive in moist, well-drained soil, ideally rich in organic matter. They prefer partial shade, mimicking their natural habitats in meadows, woodlands, and along riverbanks. When planting, set the bulbs in autumn, spacing them a few inches apart and at a depth of about three times the height of the bulb. A helpful tip: plant the bulbs on their sides to prevent water from collecting in the hollow stem and causing rot—a common challenge for gardeners. Over winter, the bulbs remain dormant underground, then send up slender, grass-like leaves and flower stalks as the weather warms. Fritillaria typically bloom in early to mid-spring, bringing a touch of wild beauty to gardens and natural spaces. After flowering, the plants produce distinctive seed pods, and the foliage gradually fades as the bulbs prepare for another cycle of dormancy. Fritillaria are generally low-maintenance, but they can be susceptible to slugs, snails, and the dreaded lily beetle. Good air circulation, mulching, and regular inspection can help keep these pests at bay. In heavy clay soils, amending with grit or compost improves drainage and helps prevent bulb rot.

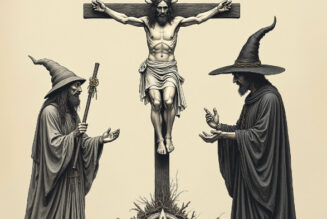

Beyond their botanical charm, Fritillaria hold a special place in witchcraft, folklore, and magical traditions. In ancient Celtic and British lore, the snake’s head fritillary was believed to be a flower of transformation and protection, its checkered petals symbolizing the balance between light and shadow, life and death. The plant’s association with snakes—creatures of rebirth and wisdom—further enhances its reputation as a powerful ally in spiritual work. In some regions, it was said that Fritillaria grew where fairies danced at dawn, and that the flowers’ nodding heads were a sign of their secret presence. Traditionally, Fritillaria was used in rituals to ward off negative energies, break hexes, and invite renewal during the spring equinox. For example, a simple ritual might involve placing Fritillaria blossoms on an altar with purple candles and amethyst crystals, focusing on intentions of healing and transformation. Some practitioners add dried petals to spell jars or charm bags for protection, or to encourage personal metamorphosis—carrying them as a talisman for courage during times of change. In folklore, it was believed that hanging a garland of Fritillaria above the doorway would keep mischievous spirits at bay, while planting them near the home invited blessings from the fae.

The flowers are also thought to attract fae and nature spirits, making them ideal for offerings or for enhancing communication with the unseen realms. In some old herbal texts, Fritillaria was listed as a plant of sorrow and remembrance, its drooping blooms said to weep for lost love or fallen warriors. Yet, its early spring emergence is seen as a sign of hope and new beginnings, making it a cherished addition to rituals celebrating rebirth and the turning of the wheel. A lesser-known fact: in the Victorian language of flowers, Fritillaria symbolized majesty and enduring love, and was sometimes included in bouquets for secret admirers. Whether used in spellwork, as a ritual decoration, or simply admired for its mystical beauty, Fritillaria weaves together the worlds of nature and magic, offering inspiration to any witch’s practice—and delight to any gardener who welcomes its enchanting blooms.